Writing Tomes that your Player will Read

- Edwin McRae

Tomes and how to use them in your Indie game.

My definition of a ‘tome’ is any piece of text that can be read in the quiet moments of a game. They can be read at other times as well, in the thick of battle if your player wishes, but the comprehension isn’t going to stand up to the test. Have you ever tried to play tennis whilst reading a novel? Ever tried to read a blog post while your toddler daughter is whining that her elder sister has chocolate bits in her half of the cookie and she doesn’t?

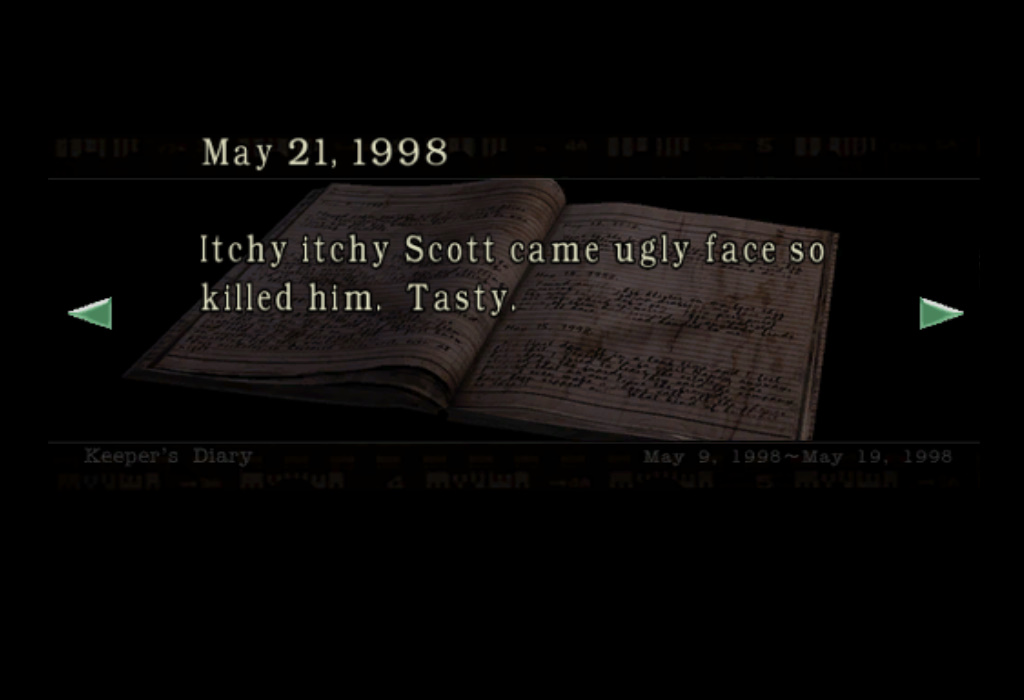

We had to overcome this problem in Path of Exile, in fact. Not the chocolate bits in the cookie issue although I’m sure that’s happened more than once in the GGG kitchenette. Our first shot at tomes resulted in some Karui carvings situated along the coastline of Act 1. Their purpose was to tell the story of the Karui invasion of the southern coast of Wraeclast and why they abandoned the area later due to some pretty grim and dark happenstances. They carvings had pop-up text and worked really well, apart from one thing. While reading them, the player could still be attacked by any passing zombie, sand spitter or rogue scavenger. Being assaulted is not conducive to relaxing reading. What’s the domestic equivalent? Um...trying to catch up on your emails whilst your dog humps your leg.

We later rectified this problem, creating ‘safe zones’ where the player could read these story glyphs in peace. Shavronne’s Diary in Axiom Prison, that was the first one. A self-contained area completely devoid of monsters. We carried this tradition on with Izaro’s Labyrinth and Daresso’s Arena, forging antechambers where the player could soak up the lore in peace before entering the frenzied violence of the area beyond.

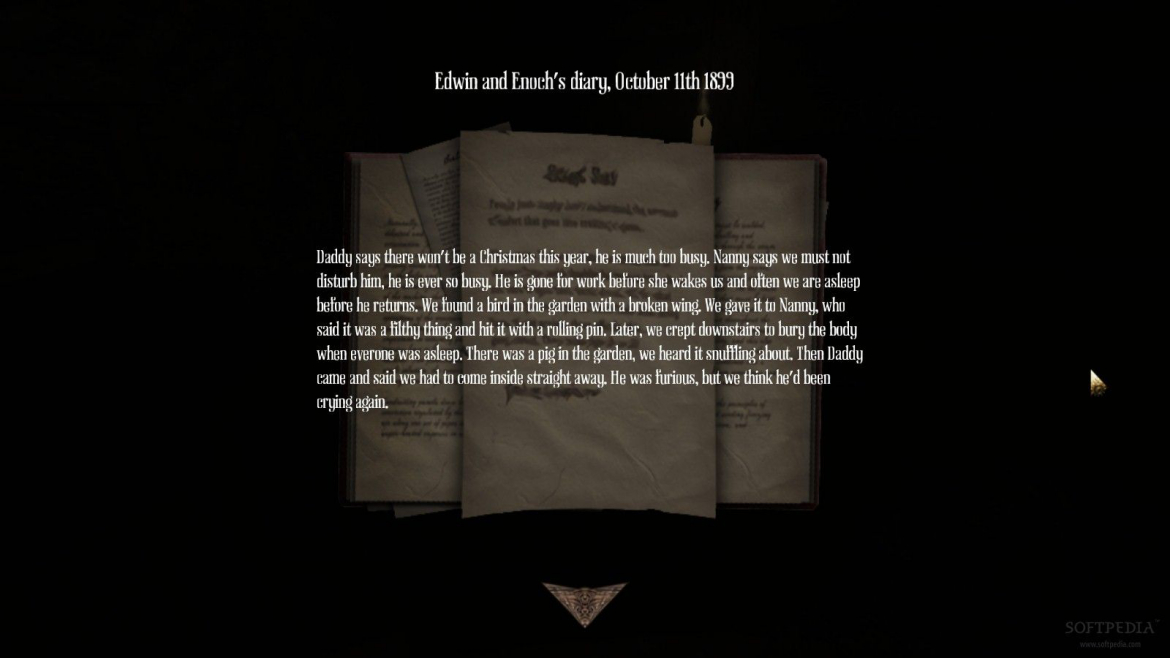

Machine for Pigs takes a different approach. Whenever you click on one of the many single-page documents littered about the game, you are drawn into a full-screen pop-up.The game freezes while you read the various histories of the great machine and the nefarious circumstances under which it was constructed. And these tomes actually serve two purposes.

By reading them you gain an understanding of why the world is the way it is and how your actions, as a player, might affect that world.

They provide much needed oases in a desert of fear and survival. No survival horror wants their player to get used to being scared. Being used to fear isn’t all that different from not being afraid at all. Tomes provide rest periods where stress can subside, making the subsequent tension and anxiety even more palpable. There’s a reason why rollercoasters go up and down and not just straight up. Well, gravity is the other one.

Now, let’s backtrack for a moment to talk about the various shapes and shades these tomes can come in. At their simplest, and worst, they are the hefty, multi-page documents that litter games like Skyrim. Verbosely written, high fantasy mini-epics. I believe it’s a hangover from early RPGs like Baldur’s Gate that were graphically simple and slow-paced. Those old RPGs needed that kind of heavy reading to help make sense of the gameplay. But in a high-action 3D RPG you’re asking a player to study a textbook on medieval history whilst in the thick of a battle. No wonder my eyes glaze over at the mere sight of these dusty works, that is unless I get to hit something with them. From the sheer size and weight of some of those Skyrim tomes, I’d likely do some serious damage to.

My rule of thumb is this…

“If you can say it in under 100 words, it’s a story glyph. If not, leave it out of your game.”

That’s what complementary story products are for. Short story collections, comics and novels set in your game world. Don’t bury your gameplay under tons of reading. Infinity Blade did this brilliantly by having Brandon Sanderson right novellas that linked the three games together, giving you all of story context you could ever want. And the games are much better for it.

Tomes can vary depending on your game context. Leather-bound books, scrolls, tattered parchments...these all work well in a fantasy setting. If your game is futuristic, perhaps cyberpunk, then tomes can be digital. Take the myriad of ebooks and emails that you can read in a game like Deus Ex: Human Revolution.

You need only look around at our present day world to witness the sheer weight of text that surrounds us, from the ingredients list on the back of a muesli bar wrapper to the health notices that festoon a doctor’s surgery.

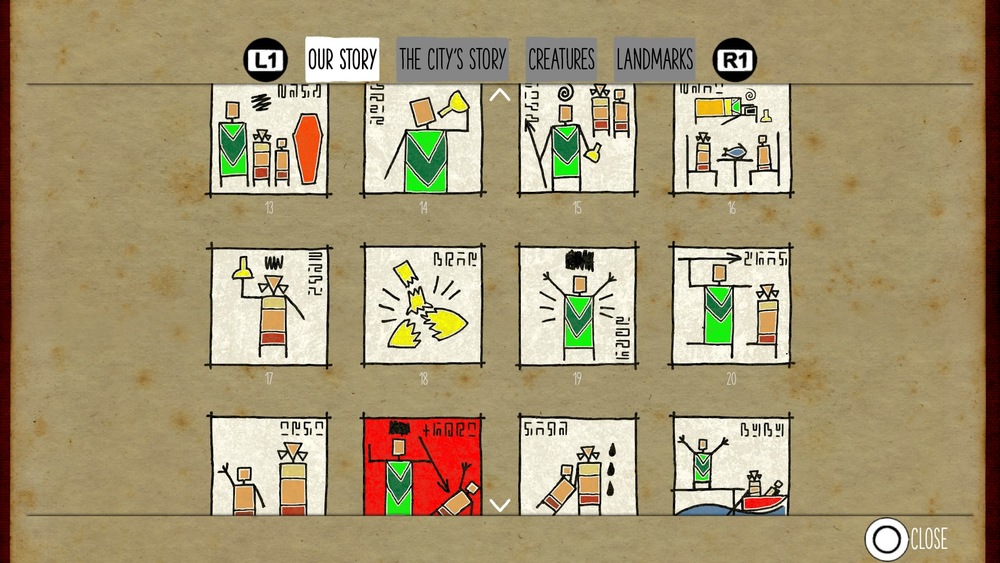

I know this blasts my previous definition out of the water, but tomes can also be purely visual, like the little illustrations that you can collect in Submerged. These illustrations tell the story of how the only two ‘human’ characters, Miku and Taku, came to find themselves in the flooded ruins of an post-apocalyptic city, Taku injured and Maku fighting to save his life. They also do a good job at explaining how the city was ruined in the first place.

Interestingly, the developers of Submerged have freely admitted that their collectable illustrations were due to budgetary restraints. They were hoping to have cutscenes but simply couldn’t afford them, so they settled for cheap and easy illustrations. The result...a far more poignant expression of backstory than cutscenes could have ever achieved.

But be careful about how many tomes you have in your game, and what purpose they’re serving. One of my many criticisms of Human Revolution is that it swamps the player with tomes. And when you take a closer look at them, only a small number are pertinent to what actually happens in the game. Actually, the same can be said of Baldur’s Gate and Diablo. Interesting stuff, but did I really need to know it? The fact that I can’t remember any of them is probably ‘enough said’ on that front.

The best kind of tome does two things.

1. It provides a concrete piece of information that will help the player complete the game.

2. It builds the player’s understanding of your game world.

Human Revolution does the former by providing security codes in emails and on the digital notebooks that can be looted from fallen foes. It does the latter by increasing your understanding of important in-game characters like Hugh Darrow. However, Human Revolution also delivers an abundance of story glyphs that do neither. Most emails reveal nothing more than the day to day minutiae of people leading near-future lives that differ so slightly from our own as to be totally mundane. Honestly, you’d have more fun reading the emails in your Spam folder.

And mundane story glyphs are dangerous because they deter a player from reading any story glyphs in your game. If 4 out of 5 glyphs are mere trivia then they’ll just flag the whole ‘reading thing’ in favour of more amusing pastimes like hacking door-codes and blasting baddies without a caring a jot as to who they are or what they had for breakfast. Actually, unless the player or someone they know is on the menu, no-one needs to know what your Bosses and MOBs had for breakfast.

So...tomes are an efficient and economical method of delivering story without getting in the way of gameplay. They can provide hints and tips to the player whilst building and deepening their understanding and appreciation of the virtual world they are experiencing. The virtual world you’ve created for them. But keep them short and sweet, and use them sparingly.

And most of all...make sure they’re well written. If you’re hiring a writer to produce tomes for you, check to see if they have a background in flash fiction, copywriting for the web, or at least short stories. Don’t hire a novelist to write your story glyphs. That will end badly, for everyone. I’ve seen it happen in person...more than once.

One last note on tomes. If you have a linear plotline that you want to somehow include into your non-linear game, hack that plotline into pieces and mix them up on your kitchen table. Like, literally, look at your plotline and write every key scene, moment, idea on a series of cards and then throw those cards down on a table in no particular order. Then turn each of those story fragments into a self contained story glyph.

For instance, if you want to make a game out of the first Alien movie, you could take the moment where the baby alien bursts out of John Hurt’s chest and write it as a post-mortem medical report that the player finds in the medbay. With a bit of creativity, and bashing one’s head against a keyboard, any dramatic moment can be converted into a tome that can be read at any time in your game and will still, when combined with others, add up to a complete and horrifying story. And better yet, you have a bundle on art and animation, because all the expensive CGI happens inside your player’s head.

I’ll say this sort of stuff a lot, so please bare with me. When writing for games, this point can’t be reinforced enough.

Lay out the story pieces and let the player solve the narrative jigsaw puzzle for themselves.

And in this instance, those piece can be tomes.

About Edwin McRae

Edwin is a narrative consultant and mentor for the games industry.