Designing game environments that are rich with story

- Edwin McRae

Environmental Features

This is a bit of a ‘catch all’ phrase to cover story glyphs that don’t neatly fit into the categories of tomes or flavour text. And the key difference is that environmental features are non-interactive. They’re part of the scenery that the player can look at or listen to but can’t ‘touch’.

I’m going to harken back to an earlier example I used. The scene where the baby alien bursts out of John Hurt’s chest in Alien. What if, no matter how much Captain Dallas scrubbed and scrubbed, he simply couldn’t get the blood stain out of the upholstery?

In ‘Alien the game’, the player could see that blood stain and know that something pretty bad went down there. They can’t do anything to the stain. It won’t open a secret hatchway if pressed or cause some sort of xenomorphic flesh-eating lurgy if touched. It’s just there to say, ‘someone died here’ and that there’s danger on this seemingly abandoned starship.

Submerged uses environmental features in a subtle and clever fashion. The flooded ruins that Miku navigates thrive with ocean life but it’s soon apparent that this ocean life is ‘wrong’ in some way. The whales are the most telling example.

At first glance they seem perfectly normal but closer inspection reveals green algae upon their skin and a ragged, pitted aspect to their head and fins. The whale seems energetic and ‘healthy’, yet it’s clearly been changed by something biological and insidious.

The player who notices these abnormalities in the wildlife is forewarned to the danger that lurks amongst these ruins. Infection leading to transformation, at threat that soon manifests in Miku herself.

Similarly effective are the environmental story glyphs in The Stanley Parable. Would you go through a door that is completely surrounded by arrows that visually scream ‘go inside!’ at you? One of them is even decorated with carnival lights!

In this case, the visual feature is backed up by the narrator who is also urging the player to go through the door. But the narrator isn’t needed. The door does all the storytelling you need. Someone desperately wants you to go through that door, and that level of desperation seldom spells good news for the person who succumbs to it.

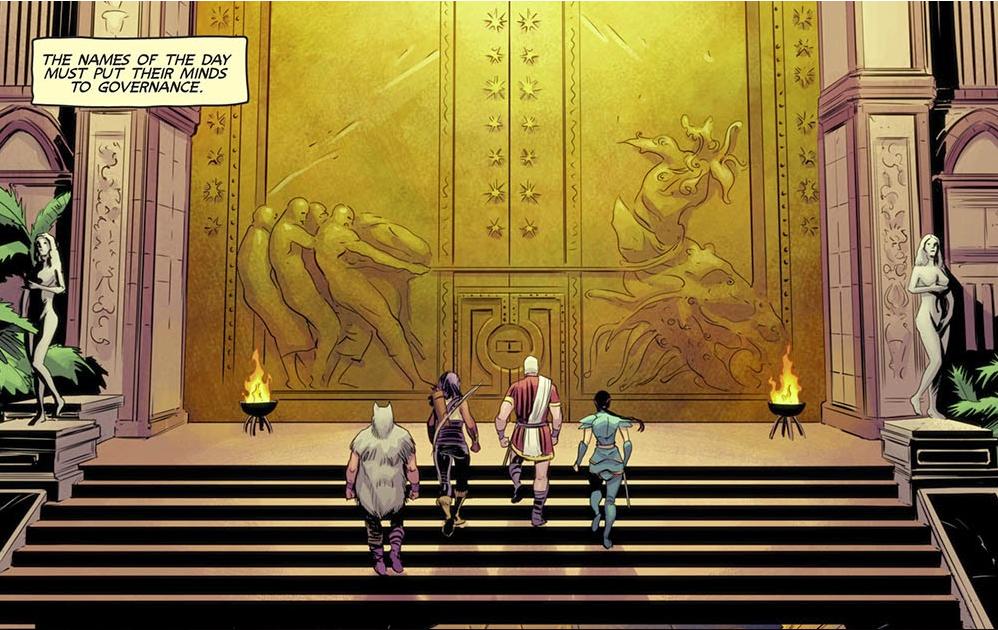

Environmental storytelling is a big part of a game like Path of Exile. The mud and blood of Daresso’s arena, a snapshot of a Duelist’s life, forever killing for the pleasure of the crowds. The fire and lava of Kaom’s kingdom, when coupled with towering Karui carvings, represents his fury and narcissistic belief that he is the only son of the war god, Tukohama. Body parts lie around cooking fires and dismembered victims hang from spikes on the Cannibal Coast. Emaciated corpses are piled high in the Solaris, juxtaposed with the steampunk experimental equipment that has claimed so many in the name of ‘science’. Yes, these are pretty grim and repulsive scenes but that’s Wraeclast for your. A land steeped in brutal ambition and tragic hubris, a theme most clearly captured upon the doors of the Sceptre of God where men struggle in a tug of war with the Lovecraftian monstrosity they have harnessed and are striving to enslave. A warning sign that some things are best left alone.

The thing is, you’ve got to create environments for your game anyway. Gameplay can’t exist in a void unless your game is about an astronaut floating through space, trying to stay alive until she is rescued. Well, even that scenario needs some environment. Her space suit. The stars. Other cosmological entities shooting by. So what I’m saying is this...

If you have to create an environment you might as well make one that’s meaningful.

The trick is to step out of purely mechanical thinking...this platform goes here and moves at this speed so that it’s difficult but not impossible for the player to jump onto...and into what I call ‘situational thinking’. We’re in an ancient catacomb beneath a ruined cathedral. And there’s giant spiders. Well of course there’s giant spiders. There’s always giant spiders, right? The walls are decorated with the bones and skulls of long dead believers. It’s an Ossuary. So this platform was constructed to allow the monks to transport these remains to various parts of the catacombs. It made their job easier. But hold on...why is it so hard to get from one platform to another? That’s got to be a serious design fault if these monks were trying to make their jobs less difficult. Ah, well time had taken its toll on the great machine that grinds away behind the walls. Everything’s out of sync due to rust and bits falling off over the eons. And then there’s the curse, of course. I mean, these monks, they didn’t die peacefully in their beds. Poor monks in video games...they tend to get a rough deal. Always delving into secrets that end up getting them all killed, usually in gut-wrenchingly horrendous ways.

That’s just scratching the surface but hopefully you can see what I mean. Those platforms become part of someone’s ancient masterpiece, now masterless and decaying due to the obsessions and follies of the past. The area now has ‘narrative weight’ that a player will be able to feel when they enter the place. If you’ve ever been to Salisbury Cathedral or Edinburgh Castle or Alcatraz, you’ll know what I mean. You can literally feel the history when you walk into the place. It’s a palpable weight, not on your shoulders, on your very soul. That’s the power of environmental features. They can turn your functional series of platforms, corridors, locked doors and traps into something that reeks with historical atmosphere. And when it comes to dungeons, they literally should reek. Unwashed bodies, buckets for defecation, and the mildew...those places would’ve stunk to high heaven.

Of course, for Indies, there’s always the question of budget. Bespoke art assets are really expensive to make. You need only take a stroll through the flying city of Columbia in Bioshock Infinite to see just how much money can be spent on purpose-built art assets. The place is stunningly beautiful and a real testament to the power of environmental features. But I shudder to think how much money got spent on those environments, most of which you only travel through once. Financially horrifying.

Yet there are a couple of tried and true ways that Indies can now create environments that are rich with story yet won’t cost the total GDP of a developing nation to create.

Asset stores

They're are a thriving business these days and games like Path of Exile have made the most of them. Of course, the danger with using off-the-shelf assets is that they either come with very prescribed meanings or with no meaning at all. The latter is more common as asset creators will tend to make one-size-fits-all pieces because they’re the ones most likely to reach the widest audience. But here’s the trick. Curation. It’s not the assets you have that matters, it’s how you arrange them.

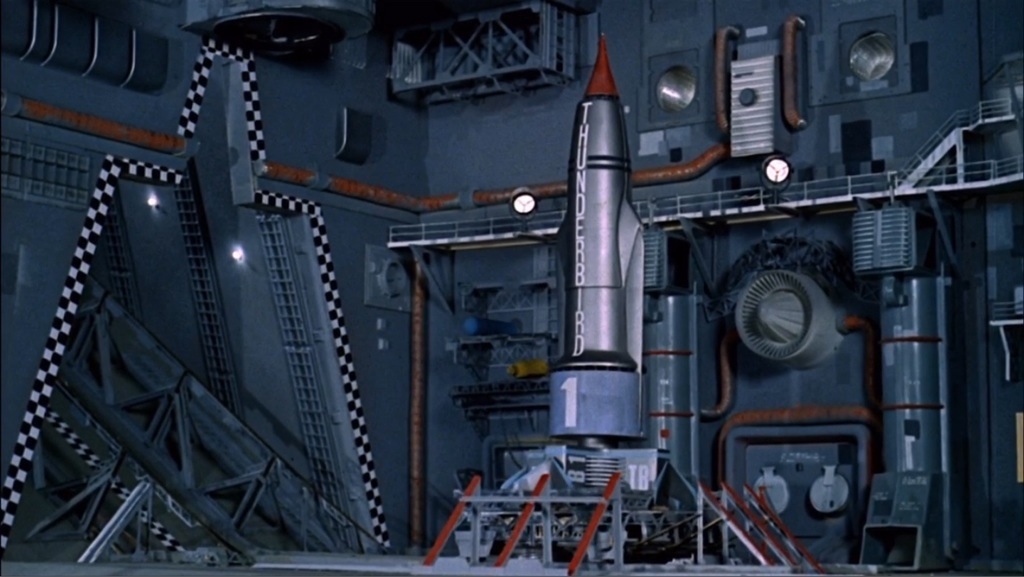

Let’s see if I can give you a more concrete example here. I recently had the pleasure of escorting my partner and young daughters through the Thunderbirds studio at Weta Workshops in Wellington. The sets are all created in miniature, and to my surprise, they’re made predominantly out of ‘found’ items. The creators scour secondhand stores, refuse centres and online trading sites in search of general detritus they can repurpose and combine into structures like The Hood’s ship. Honestly, when you look up close at the thing, it’s just a mass of old computer parts, air-conditioning units and any other sort of mechanical ‘waste’ you can think of. Taken as a whole, it’s a masterpiece of postmodern engineering.

As an aside, it’s an ongoing challenge for the Thunderbirds designers to include a classic 60s lemon squeezer in every episode. Can you see it?

This is the kind of ingenuity that’s required when building a meaning-rich environment out of stock assets. We’re talking juxtaposition and Gestalt here.

Juxtaposition = The meaning formed by placing one object next to another.

Gestalt = The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Before you dive into your environmental design with all of those freshly purchased assets, have a chat to a museum or art gallery curator. Pick their brains about their thought processes when it comes to arranging a disparate collection of items into something that has meaning and emotional resonance for the visitor.

As another aside...sorry, I do these a lot...you’re curation shouldn’t stop at the non-interactive elements in your game environment, the rocks, trees, waterfalls and hanging cages containing the skeletons of those who foolishly disagreed with the monarch at the time. Also consider the MOBs. How creatures and baddies congregate, that’s just as important as the panels and screens you place in the starship bridge or where you put that blood pool in relation to those mangles corpses.

In the early days we hit this snag in Path of Exile. Along the coast we had zombies and hostile humans standing literally side by side. What happens usually when you place a zombie next to a human? Lunch...for the zombie. But in this case the zombies seemed fine with passing up an easy meal in favour of a much more difficult and likely fatal dalliance with the player. Not every player will notice these kinds of oxymorons, but for the players that do, their experience of that area is ruined. Tragedy becomes comedy, and if your game is a dark fantasy or survival horror, you really don’t want that!

I learned a lot from that experience and was able to address the issue in Bloodgate: Age of Alchemy. For that game we designed the monsters to exist only in certain environments. Mutant werebears inhabited mountains while mutant werewolves inhabited forests. Fishmen needed to be adjacent to water. Mutant bugs tended to be underground, along with infected miners. We kept a close eye on the juxtapositions of our MOBs in an endeavour to make sense of our in-game population.

The key thing to remember, for both landscape elements and MOBs, is that they must have an existence that makes sense in total isolation to the player. When you go tramping, or hiking for you American types, you should hopefully realise that the wilderness isn’t just waiting for you to turn up so it can put on its ‘nature show’. For the most part, nature honestly doesn’t even notice that you’re there...unless it’s hungry or you’ve just stepped in its nest. Design your environments so that they have their own ‘story’, a life of their own that makes total sense irrespective of player interference.

This can be done through careful curation of stock assets, bought off-the-shelf, or the other way I’m going to talk about now.

Bespoke assets.

You can always take the ‘less is more’ approach with your Indie game. So rather than go with all of the bells and whistles of a 3D, hyper-real extravanganza, go for 2D or heavily simplified and stylized 3D.

Amnesia: Dark Descent and Machine for Pigs are simplified in that they don’t have a heap of moving parts to deal with. There are very few MOBs in this game so what budget there was clearly got spent on developing the variety and atmosphere of the environment. And even then you can see that a ton of stuff gets repeated and reused. But the overall effect is of brooding malevolence and that pervading sense that the ‘walls are closing in on you’. The situation is similar with Gone Home, and even more so with the Stanley Parable. Take away the MOB animations and you suddenly have plenty of resources left over for environmental design.

But hey, at the end of the day, I’m a writer. It’s not my job to tell you where to spend your art budget. Oh wait...it actually is my job to tell you where to spend your art budget, because being a narrative designer means coming up with the concepts in the first place. So if you want a cheap but effective art style that stands out from the pack and has the capability of telling its own story, the job doesn’t start with your artists, the job starts with your narrative designer.

Arguably, that’s very much that case with The Stanley Parable. From the mundane offices at the beginning to the surreal scenarios ‘behind the scenes’ of the game, every environment is a story environment. In fact, it’s even more the case with The Stanley Parable because the environments are meant to have been created by the narrator. A Storyteller. You’re walking through his imagination, following his beaten pathways or leaping from them into his half-baked ideas and constructs. And if you’ve played The Stanley Parable, which every game and narrative designer should, you’ll know that even the most thoroughly realised environments in that game are comparatively cheap and easy for a 3D artist to create.

There’s a concept I believe too many game devs misunderstand. That concept is immersion. I’m going to talk a lot more about this later when I delve into the weird wonders of world building. But for now, let me pose a question to you.

How immersive do you find reality?

When you step out your door and face the world, whether it be a forest or a parking lot, can you honestly say that you are 100% immersed in that moment? Is your looming apartment building more immersive than a black and white sketch of Gotham City? Is your forest more immersive than the creepy claymation woods in The Nightmare Before Christmas? Probably not.

Yet AAA games seem hell-bent on forging ‘realism’ even in the most fantastical of worlds. But the problem with hyper-reality is that every single detail is provided for the audience. Every hair, every speck of blood and notch on the battleaxe, every fly and every flower. The result...absolutely no room for human imagination.

And guess what? Short of putting your player in real, mortal peril, like threatening them with a knife in a dark alley, you’re not going to get better engagement and immersion from them than when you spark their imagination.

I’m going to use two gamebooks as my examples here, twin blades with which to skewer your brain like a spit-roast. It won’t hurt...much.

Example 1 - Lonewolf.

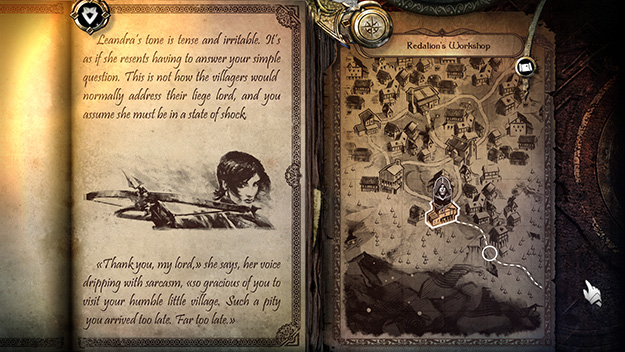

I played every single one of the Lonewolf gamebooks as a teenager and twenty-something so I was naturally a bit ‘geeky squee’ excited when a fancy Lonewolf app was released for iOS. And it was a beautiful thing to behold except for one major and very expensive mishap.

Gamebooks are for text-lovers. You have to be as much a reader as a gamer to enjoy a gamebook. But when it came to the combat system in Lonewolf, all that yummy text and symbolism crossfaded into a fully 3D, third-person turn-based battle scene. From black and white to full colour, from imagined to fully realised...in the eyes of the developer.

And the result? A jarring experience that totally destroyed my enjoyment of the gamebook. Why? Because a full bells-and-whistles RPG combat system leaves very little room for imagination. It switched me into a totally different frame of mind, from visualisation to reaction, from contemplation to action. When you read, you’re on your own clock, pausing to consider what you’ve read, absorbing the words at your own pace. When you’re in a 3D combat system you’re on developer time, having to react or die. And once you’ve switched from contemplation to survival it’s very hard to switch back. Impossible for me. My eyes slid off the pages while my fingertips itched for interaction. I switched the game off and never went back.

Lonewolf suffers from a total clash of styles. And when you have a clash of styles, you have a clash of psychology.

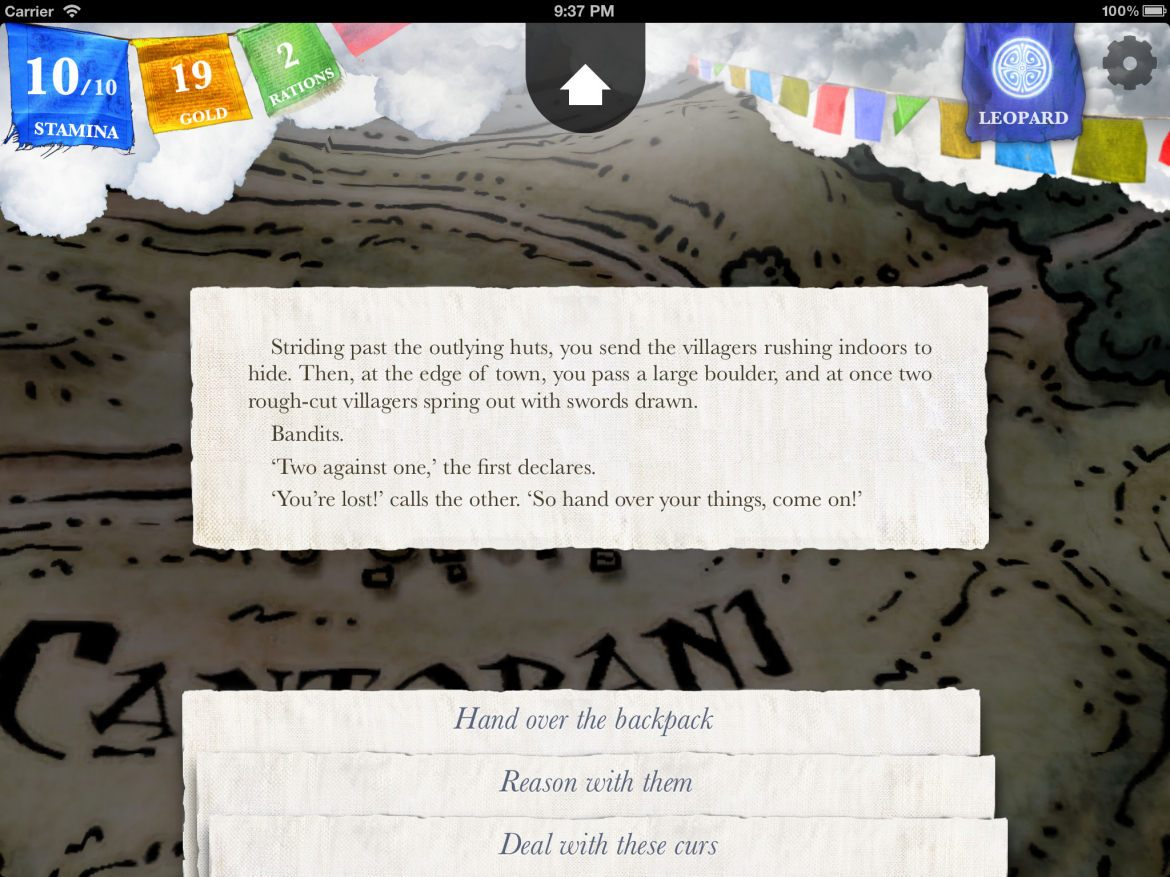

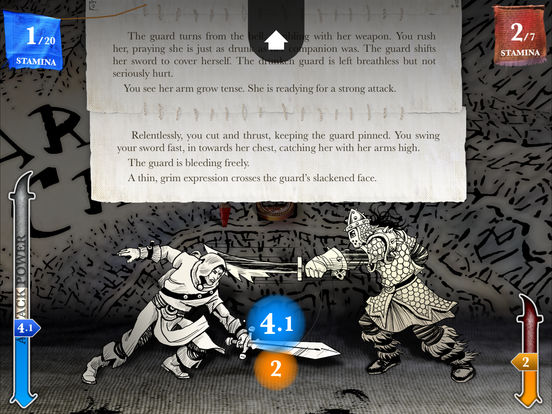

Example 2 - Sorcery!

Back in the day I also owned and played all of Steve Jackson’s Sorcery series. Whilst the context is similar to Lonewolf, the execution is like chalk and cheese. Sorcery has both a combat system and a magic system. But where Lonewolf broadsided me with attempted realism, Sorcery welcomed me with the open arms of abstraction. Its combat is 2D, using simple, illustrated versions of my character and my enemy. Each move is described in text and the whole thing feels much more like a tabletop RPG experience than it does a video game.

Likewise with the magic system. It uses floating letter combinations to construct magic words.

Fundamentally symbolic and linguistic.

The difference in overall engagement and enjoyment is remarkable. The transition between reading and combat/magic is seamless. At no time was I jolted out of my contemplative, interpretive mindset. There’s no timing urgency with the combat. It’s a calm, measured battle, more akin to chess than Final Fantasy or Darkest Dungeon. Don’t get me wrong...there’s still tension and excitement but mostly because I’m imagining the battle in my head. And it’s that act of imagination that causes the immersion.

With Sorcery, I felt so comfortable that I was able to lose myself in the story and experience. With Lonewolf, the combat system shoved me into a strange, hostile environment, a situation they made me feel very aware of myself.

Whether it be a creation in Minecraft or interpretation in Journey, the players immersion is one of imaginism, not realism. Please, build your game environments with this in mind. Immersion is literally when you place yourself inside of something, whether it be a pool of water or a poignant visualisation. And you can’t place yourself inside of something when there’s no room to fit.

Ok, so just to hammer this point home one last time….

Curation

Imagination

Curate your off-the-shelf assets in such a way that every placement of every piece means something. Are the Grecian Man Statue and the Grecian Woman statue facing towards each other or facing away from each other? Two generic objects, but when it comes to their ‘relationship’, that’s where story lurks.

And if you’re going bespoke, forge an art style that leaves plenty of room for player curiosity, interpretation, and even creativity if your game allows it. Spark the player’s imagination and they happily lower themselves into your evil genius lava pool...the one where the mutant sharks have lasers on their noses.

Oh, and get your narrative designer involved in that process from the very beginning. Yes, artists are probably better at visualising the details of a scene, although not always. You only need to read one of George R R Martin’s feast scenes in Game of Thrones to understand just how visual and detail-oriented writers can be. But your writer has one advantage that your artist likely does not have. An obsession with story. If they’re anything like me, they see story everywhere. They don’t buy a mug because it holds the right amount of water or beer. They buy a mug because it has Darth Vader on it and that somehow imbues the glass with ‘dark force resonance’ thereby making it a magical vessel from which to drink, one that’s bound to induce vast epics of dark fantasy prose. Ok, that’s my mug I’m talking about, and I made the mistake of putting it through the dishwasher so Darth is now missing half of his face. Hopefully though, you get the picture. Your writer can ensure that your environmental visualisation process is steeped in story. Rich narrative that your artist can then mould into stunning eye candy.

Don’t get me wrong. I think artists are marvellous people who create pure magic. I certainly can’t do what they do. But if you want a game environment that veritably screams with history, meaning and lore, then…”Don’t bring a knife to a gunfight.”

Let your narrative designer do the other half of what they’re good at. Design.

If you're keen to know more about the general principles of narrative design, I have this handy little book on the subject.

Thanks for reading. :-)

Edwin

About Edwin McRae

Edwin is a narrative consultant and mentor for the games industry.