Building game worlds for indies - Stimulation versus Imagination

- Edwin McRae

Video games enable people to explore fictional worlds in a way that books, films and television have never been able to achieve.

Hands-on interaction with a fictional world!

I grew up on a sheep farm in Southland, about as far from ‘civilization’ as you can get in a Western country like New Zealand. Compared to many, it was an idyllic childhood. Plenty of room to breath and explore. But after reading The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe I searched that farm, top to bottom, for a portal that would allow me to escape into a wondrous fantasy world. A world where I didn’t have to slog through mud in my gumboots to shift an electric fence. A world where I didn’t have to deal with bullies, rugby culture, girls that just weren’t interested in me that way, dreary tracts of farmland, yawning through my parents’ local choir recitals (sorry, Mum) and generally being bored and frustrated with what ‘normal life’ in rural Southland had to offer.

I didn’t want to be just another farm boy. I wanted to be the hero of my own epic saga.

I never did find that portal to Narnia, but what I did find, under the Christmas tree one year, was an Atari 600XL. Here was the doorway to the fictional worlds I’d so longed to play in, to adventure in, to be myself in. In these clunky, barely decipherable 16k lands I could be a character in a story rather than sit in the armchair after school every day to passively soak in episodes of The Flintstones, The Smurfs, Danger Mouse and Mighty Orbots. I could be part of the adventure rather than watch the characters of Dungeons and Dragons have all the fun.

I could roam ruined landscapes and dungeons in Wizards Crown. I could fight my way to world martial arts stardom in International Karate. I could protect the helpless in Defender and rescue my beautiful girlfriend in Double Dragon. Hell, I could even be a murderous, gold-grasping bible-bashing Conquistador in Seven Cities of Gold.

Video games opened the door to Narnia. So many Narnias.

In fact, one of the finest moments for me, a signpost along the road from passive consumer to active gamer, was when I watched The Last Starfighter and then was able to be that last starfighter in the video game that came out in 1984, same year as the film.

That, to me, is the defining feature of video game fictional worlds that set them apart from any other medium. You can inhabit them.

Of course, one can argue that you can come close with tabletop roleplaying games, LARPS and some forms of interactive theatre, that you can surround yourself in a fictional world, immerse yourself in a collective imagining of Narnia.

Imagination

There’s the rub, as Shakespeare would say among his wordy, evocative descriptions of fancied times and places. Ironically, he burned The Globe down when he tried to shortcut imagination, when he tried to get too ‘realistic’ and involve an actual canon during his 1613 performance of All is True.

But then, until the dawn of the digital age, attaining realism in storytelling was fraught with such dangers.

Just ask Brandon Lee who was accidentally shot dead during the filming of The Crow or the desperately unfortunate Martha Mansfield whose 1860s hoop dress caught on fire during the shooting of The Warrens of Virginia. She was burned to death.

Films have long strived for realism, for better, or worse if you ask the three extras who drowned during the filming of Noah’s Ark (1928). The international film industry, driven by Hollywood, has worked towards reducing their audience’s need to imagine the details and contexts of the story. Unlike novels that ask the reader to create the imagery of the story in their minds, films primarily seek to provide the defining vision for them. In an Avengers or Star Wars film the ensuing ‘visual spectacle’ offers up all the stimulation a human brain can take. It aims to fill your mind with that spectacle, to swamp you with stimulation so that you can literally think of nothing else.

“Whatever has happened in my quest for innovation has been part of my quest for immaculate reality.” - George Lucas

So knowing where film has gone before, and AAA game development has followed, here are the questions that every indie game developer should ask themselves before building their fictional world.

How much am I going to ask my player to use their imagination?

How much stimulation am I going to provide my players?

What balance shall I strike between imagination and stimulation?

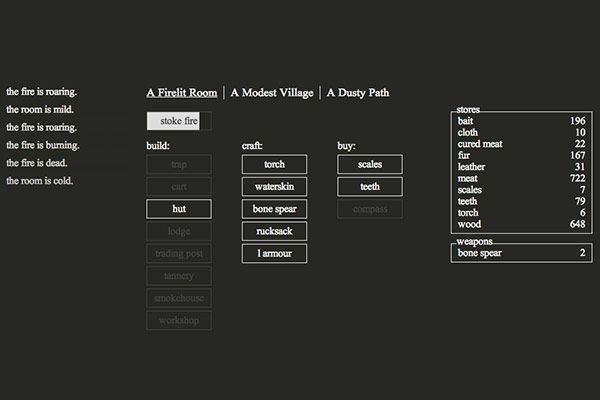

A Dark Room by Doublespeak Games provides the absolute minimum of stimulation while demanding a great deal of imagination from the player. Being a text-based town builder and RPG, A Dark Room provides information in its most basic, abstracted form. Letters and numbers. Even the game’s map, the only ‘graphical’ element, is constructed from ASCII. A Dark Room is the closest a highly mechanical game can get to the experience of reading a novel. The reader’s mind is the high resolution graphics card, processing all that imagery on the fly.

By stark contrast, Horizon Zero Dawn is an intensely stimulating experience, offering super high quality graphics and sound so that the player need never imagine what this post-apocalyptic America looks like. They can see it with their own two eyes!

The same goes for Red Dead Redemption, a fully rendered fictional world brimming with stimulation and requiring very little from the player’s own organic wetware. But it’s not a perfect depiction of its proposed fictional reality. Look closely and you’ll see that there’s nothing in Arthur’s hand when he feeds his horse.

Yes, even the most intricately realized games require players to ‘suspend their disbelief’ at times. Reality and games are still a long ways apart, but that gap, once cavernous, is closing fast. Just look at Unreal Engine 5.

As an indie you don’t have the colossal budget that Rockstar can bring to bear. You can’t afford to create an enormous world and fill it with intricate details. You have to work with limited technology and even more limited finances. That means you have to make a trade-off.

Do you create a small high-stimulation world that looks and feels as real as you can make it?

Or do you create a larger low-stimulation world where the player has to fill in the reality gaps with their own imagination?

There’s no right or wrong answer to this question. It all comes down to the type of experience you hope to offer. The important first step is that you make that choice, to mark your spot on the continuum from imagination to stimulation.

From one indie to another, I would recommend that you leverage the most incredible visualization engine yet to be seen on this planet. The human brain. It’s the best and most affordable piece of outsourcing you can ever do. And to see exactly how your player’s imagination can be leveraged to good effect, let’s look at a couple of indie games that do this really well.

80 Days by Inkle strikes a near perfect balance between imagination and stimulation. If you haven’t played it then here’s the brief product description.

1872, with a steampunk twist. Phileas Fogg has wagered he can circumnavigate the world in just 80 days. Travel by airship, submarine, mechanical camel, steam-train and more. Race other players and a clock that never stops in TIME Magazine's Game of 2014.

At first glance this is a text-based adventure game. The heavy lifting for world depiction is done through the scriptwriting. For instance, when Passepartout and Phileas pass through Rome you get a vivid description of the half-human, half-automaton soldiers that the Artificers Guild have created, and the subsequent peoples’ rebellion against what they believe is an abdominal melding of man and machine.

The graphics in 80 Days are deliberately minimal, showing only black and white illustrations of transportation and limited hue, low detail illustrations of landmarks. But the ominous atmosphere of Rome is set by the looming, beshadowed coliseum, and when combined with the text, the stark portrayal establishes a version of Rome that feels unwelcoming to the point of threatening.

This is “high imagination” storytelling at its best, but Inkle doesn’t expect the player to do all of the hard work for them.

80 Days also has a trading system where you can purchase items in one location and sell them on at a future location, hopefully for a tidy profit. This is how Phileas and Passepartout fund their trip around the world.

Recognizing that there are limits to how much even an interactive fiction fan will read while playing, Inkle drew the line here and offered up simple illustrations for each inventory item. It’s an effective moment to lighten the cognitive load as it’s pretty challenging to write an evocative and memorable piece of text for Buddha’s Tooth or a Cuban cigar. In this instance Inkle have clearly weighed the costs and benefits of their text descriptions. It takes just as many words to evoke the atmosphere of an entire location as it does to express the finer details of a single item. They chose wisely and went for visual shorthand for their items.

Yet even with the item illustrations, Inkle have leaned on the player’s imagination to fill out the experience. Instead of the high stimulation, lovingly crafted item illustration you would get for a weapon or piece of armour in a game like Path of Exile, the 80 Days illustrations are low stimulation abstractions of items. The “Lost Rembrandt” is actually just a piece of aged parchment with some barely discernible sketches on it. It’s up to the player to imagine what it would feel like to have one of Rembrandt’s lost sketches in their hand, to feel the weight of that artistic history and the prickling sweat in one’s palms of the predicted riches to come from selling such a treasure.

When it comes to high imagination storytelling, it’s about picking the most emotionally evocative details and leaving the rest to… the imagination.

Limbo by Playdead manages to do this without any words at all. This beautifully bleak game depicts a nightmarish, post-apocalyptic world through silhouette, haze and shadow. The whole game is done in black and white. The foreground is uniformly black apart from occasional water features and ruins like a broken HOTEL sign where white highlights are added.

The background shows looming dead trees or abandoned industrial buildings, but these have a gauze filter over them that render them as abstract as an impressionist painting. The overall effect is that of a desolate world infested with giant spiders, laden with macabre traps and inhabited by savage survivors who appear out of the gloom like paper puppet characters in Wayang Kulit (Indonesian shadowplay).

While a high budget, high stimulation game like Mad Max: Fury Road shows an apocalyptic wasteland in all of its stark beauty, sandstorms and cannibalized human remains included, Limbo asks the player to imagine the dying world that stretches beyond the simple 2D foreground and parallax background. For a mere fraction of Mad Max’s world building budget, Limbo evokes a comparably frightening world.

Looking back at my own narrative design projects, I took a very imagination-over-stimulation approach with Metia Interactive’s Guardian Māia. The creator, Maru Nihoniho, ultimately wants to build a 3D action adventure game with her Guardian Māia IP, and at the time of writing is in the process of realising that dream. But we had to start somewhere, with a very small budget kindly granted to us by the New Zealand Film Commission as part of an interactive storytelling fund. So we hatched the plan to flesh out the game’s dark fantasy world through a text-based interactive adventure for mobile with Māia in the starring role.

“You are about to guide Maia on a treacherous journey where decisions aren't simply about life and death. The gods are watching Maia very closely, judging her behaviors, weighing her choices. Maia's mana is at stake in many of the moves she will make.”

As we developed the Guardian Māia world and brought it to life with Ink script, we had to make careful decisions about where we could afford to offer moments of stimulation to help support the player’s efforts of imagination. We wanted to immerse the player in Māia’s world without weighing them down with lengthy descriptions of the flora and fauna, of the whenua (land) and its tangata (people). The Guardian Māia IF (interactive fiction) app is a game, first and foremost, and we wanted our player to spend more time in the action and less time in the depiction.

To address this issue character and creature illustrations were created that could be unlocked as Māia encountered those other inhabitants of her fictional world.

It takes a fair amount of text to portray a character with any level of detail, to effectively paint a face and physicality in a reader’s mind. And the reader’s memory needs to be regularly jogged with brief mentions of that physicality else a character’s look will be lost among all the other myriad details of a story. This was an instance where we decided it was simpler (and cheaper) to establish our character and creature looks visually. A gallery of character and creature portraits saved us thousands of words and spared the player some gnarly visualizations in the process.

We also created scene illustrations that would head up each Chapter of Guardian Māia to help establish the setting for each portion of the adventure. These gorgeous images were used to show the characters against the backdrop of our alternate Aotearoa (New Zealand), its lush wilderness, Māori settlements and post-apocalyptic ruins. Words can only go so far in describing the character of a land, the beauty of its nature, the intricacies of its inhabitants’ creations. In this instance our limited money was better spent on showcasing our fictional world through imagery.

Guardian Māia was an act of fantastical world building on a tight budget. We used the cheapest building material we had, words, to do the heavy lifting for our worldly expressions and leveraged more costly illustrations where words became ineffective or inefficient. Thus we managed to develop an entire dark fantasy world on a shoestring, a world that we are now able to realize in Unreal Engine in full color 3D.

So here’s the rub again, dear indie.

As you build your game world, please keep the imagination-stimulation continuum in mind. If you can’t afford to make your world “better than they could ever have imagined” then use the player’s imagination for all it is worth. Prompt them to imagine your game world for themselves.

The human brain is the most powerful visualization engine that you’ll ever have access to.

About Edwin McRae

Edwin is a narrative consultant and mentor for the games industry.